What Pa Salieu Made When No One Was Watching

When Pa Salieu arrived in Sydney last December, the idea of distance dissolved almost immediately.

Not because the journey from London is short, because it isn’t, but because Pa has long rejected the idea that geography determines connection. “There’s no such thing as far away,” he tells me matter-of-factly, sitting across from me ahead of his first Australian shows. “Other planets are far away. We’re all we’ve got.”

It is a sentiment that runs quietly but insistently through Afrikan Alien, the 11-track mixtape that marks his return after more than two years away from music and public life. Afrikan Alien is not framed as a redemption arc, nor a victory lap. Instead, it is something rarer: a work defined by patience, clarity and refusal, refusal to be bitter, reduced or categorised.

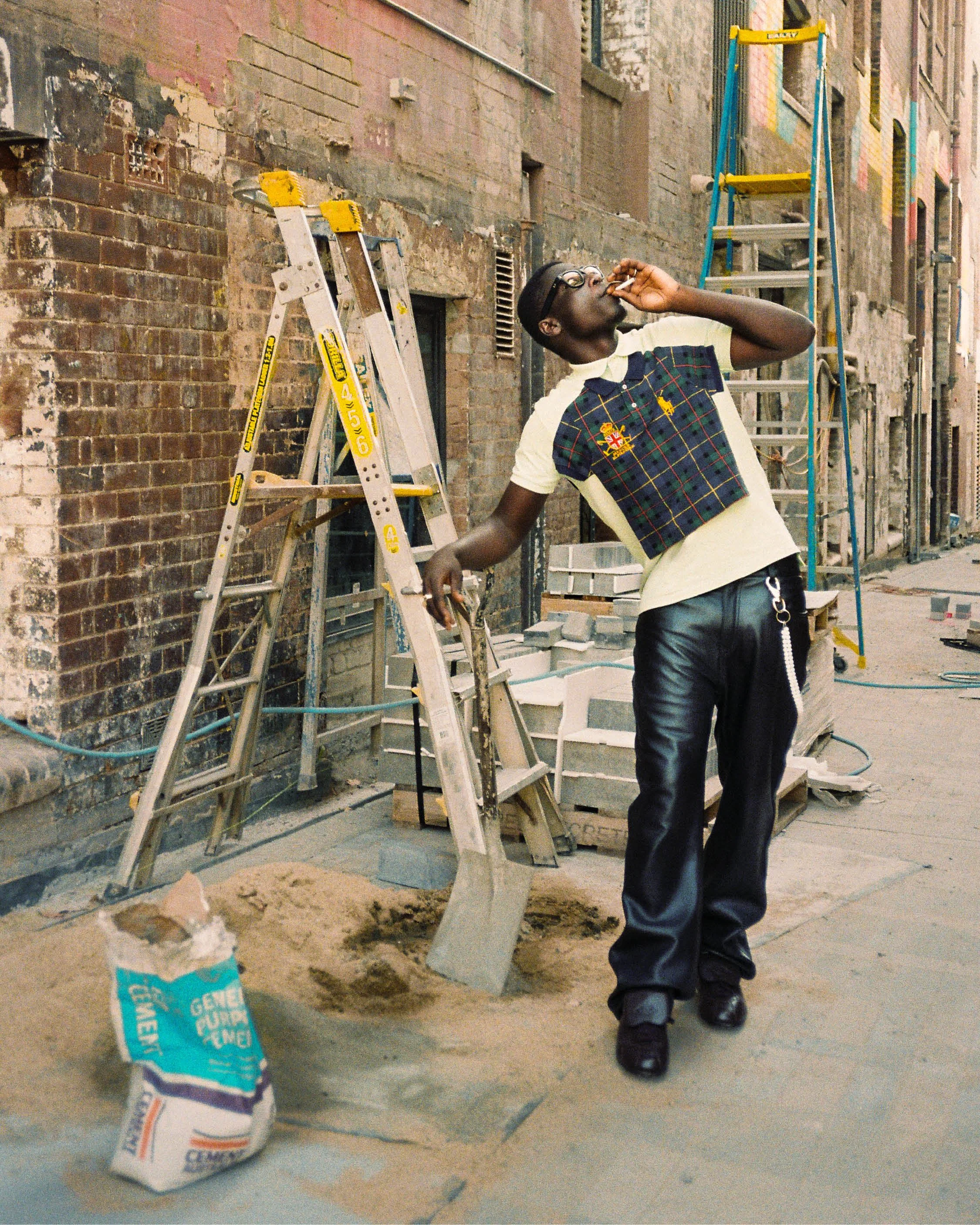

Our interview takes place in the PAM store, under bright summer sunlight that feels at odds with the weight of the themes Pa carries so calmly. There is ease in the courtyard we sat in, laughter, tangents, moments of stillness, and that ease feels earned. This is not an artist rushing to explain himself. It is someone who has already done that work privately.

Much of Afrikan Alien was written during Pa Salieu’s two-and-a-half-year imprisonment. Deprived of studios, beats and the machinery of music-making, his creative process was reduced to its most elemental form: pen, paper and memory.

“I was writing more on paper,” he says. “Every day. Even while I sleep, I’d have lyrics in my head and wake up to write them down. There’s no beats. No notes. It was more art then.”

What emerges from that period is a redefinition of what music means to him, not as content or output, but as instinct. This wasn’t songwriting as preparation for release. It was writing as survival, language captured before it disappeared.

“I never studied that, really,” he adds. “It was my passion.”

That private relationship to art shapes Afrikan Alien at every level. The project resists neat genre boundaries, drifting between Afrobeats, UK rap, jazz, R&B and experimental textures without settling. It sounds expansive because it was created without pressure to sound like anything at all.

The title Afrikan Alien is not metaphorical for Pa; it is literal, historical and deeply personal. It speaks to migration, displacement and the generational trauma that accompanies movement across borders.

Pa speaks about migration as lived reality rather than abstraction. Family members risked everything crossing seas in search of stability; some survived, others did not.

“My uncle, the one that raised me in Gambia… he was in a capsized boat,” Pa says plainly. “When locals go on a boat trying to look for a better life, it comes with big situations. It’s risky.”

While incarcerated, these stories resurfaced with new urgency. Watching the news from inside, he saw migrants stranded between borders, refused entry, suspended between land and sea. “You’re looking at the world from the outside,” he says. “From a microscopic view.”

That understanding anchors the emotional gravity of Afrikan Alien. The opening track, Afrikan Di Alie, references the transatlantic slave trade and the institutional racism that continues to shape diasporic existence. From there, the project unfolds like a living archive, documenting survival, movement and self-definition.

“Migrants is what made me,” he tells me plainly.

Despite its political clarity, Afrikan Alien never feels didactic. Its power lies in restraint. Pa is not interested in slogans. He is interested in truth.

One of the most affecting tracks on the project, Belly, predates Pa’s imprisonment. Written while he was awaiting trial, it functions almost as a message sent forward in time.

“I knew I was going to jail,” he says. “So, I wanted to make songs for when I come out.”

The phrase “feeding the belly” operates on multiple levels: material survival, spiritual nourishment, responsibility to family and community.

“It’s love,” he says. “Feeding the hunger. Feeding what’s right.”

The music video, which ends with Pa feeding members of the community, renders the metaphor literal. It is not charity as performance, but sustenance as survival. Listening now, Belly carries the assurance of someone preparing for hardship without surrendering hope.

If Afrikan Alien documents confinement, YGF (Young, Great and Free) celebrates release.

Pa describes freedom not as the absence of struggle, but as peace, internal alignment rather than external validation. “Freedom is being at peace, isn’t it?” he asks. “I understand what freedom is.”

For him, the track reflects generational consciousness. “We’re the younger generation,” he says, “but we have the knowledge of the past and the knowledge of now, so that’s always ahead.”

It has become central to his live shows, and when asked to name his favourite song on the mixtape, Pa returns to it instinctively. “Especially when I perform it,” he says. “I get a voice.”

Pa’s grounding force, both personally and creatively, is faith. Raised between Coventry and Gambia, he grew up reading the Qur’an, surrounded by mosques on both sides of his family. The concept of sabr (patience) appears repeatedly.

“That helped a lot,” he says. “Even going to Coventry.”

He does not romanticise his upbringing. He speaks openly about racism and hardship, but also of pride, lineage and folk traditions passed down without performance. His aunt is a folk singer, and Pa’s definition of folk is not genre, but transmission. Art that exists because it must.

His resistance to categorisation extends into process. “I’ll mumble, capture the vibe and add lyrics,” he explains. “It’s just like talking. Freedom of sound.”

Influence, for Pa, is subconscious. Martial arts films, nature, movement, absorbed rather than curated. “We’re always getting inspired subconsciously,” he says. “Music is the same.”

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Pa Salieu’s return is its absence of spectacle. There is no urgency to reclaim space, no insistence on narrative dominance. Instead, there is calm conviction.

“I refuse to be broken down,” he says. “Prison taught me that bitterness won’t solve anything. Acceptance led to my growth.”

That acceptance does not imply forgiveness of injustice, nor does it dilute anger. It simply refuses to allow pain to become identity.

As our conversation winds down, Pa prepares to take the stage later that night at the Oxford Art Factory. Before every show, there is only one ritual: Bismillah. Remember God. Be confident.

In a world that constantly demands performance, Pa Salieu is doing something quietly radical: he is listening. To history. To lineage. To himself.

Afrikan Alien is not the sound of return.

It is the sound of arrival.

See more from Pa Salieu here

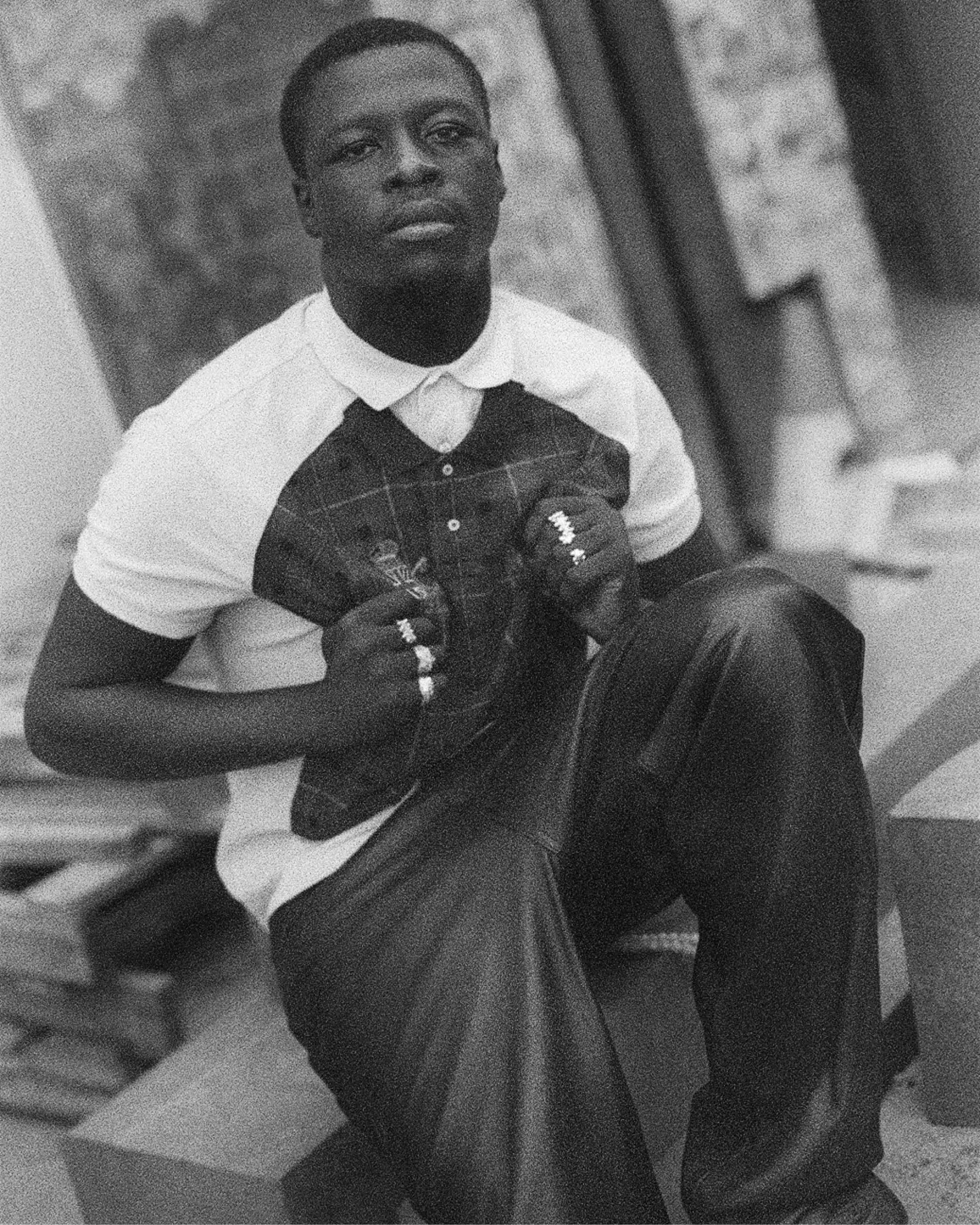

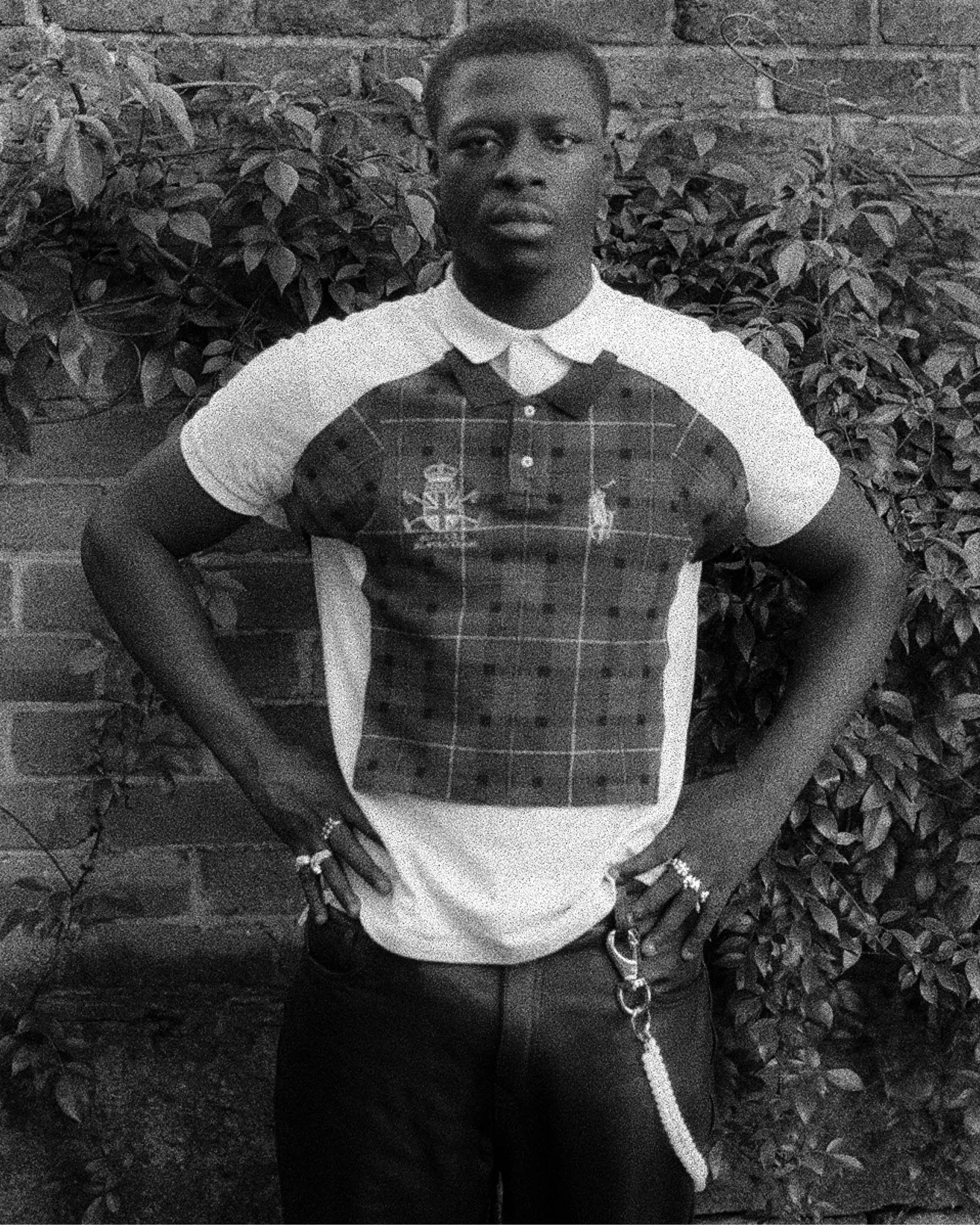

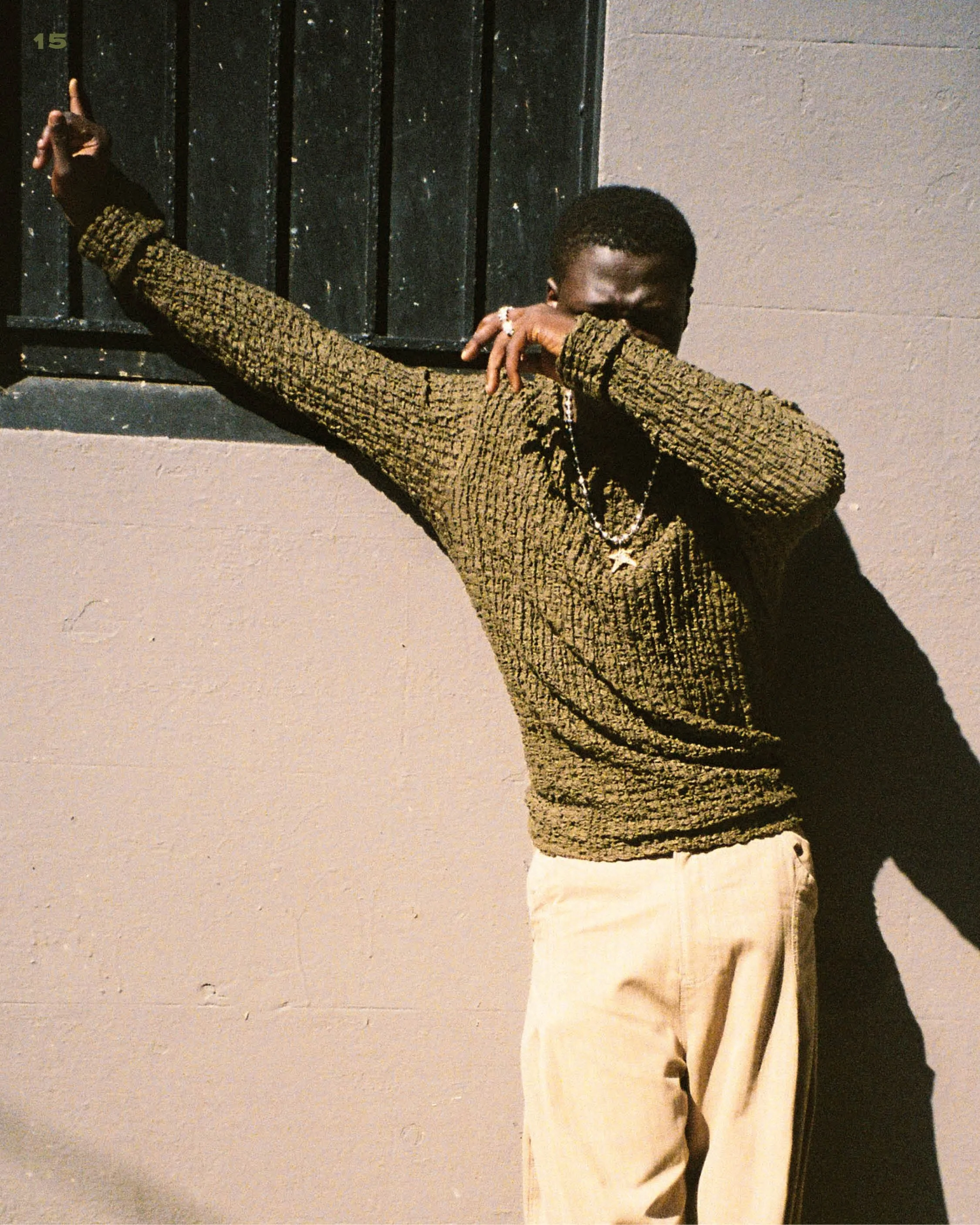

Creative Direction / Photography Reem

Interview / Editing by Reem

Styling Laura Mazikana

Styling Assist Charlotte Edwige

Video & Photography assist Enoch Ekundayo

EIC Simone Taylor

Thanks to PAM Store Sydney for allowing us to use their space

Jacket: Song For The Mute, Pants: Dallas Hurst, Shoes: Tods, Rings: tatah the label, Wallet chain: Jody Just / Dallas Hurst, Pants + wallet chain: Jody Just, Shoes: Tods Rings: talents own + Tatah The Label / Top: Song For The Mute, Pants: Dallas Hurst Rings: talents own + Tatah The Label, Necklace: tatah the label, Shoes: Tods